by Elizabeth Cunningham

Author’s Note: The exhibition and catalog Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company: American Moderns and the West inspired this series on Mabel’s life. The show opens with her birthplace and first home in Buffalo, New York. I’ve drawn heavily from Background, Mabel’s memoir about her early life, and adhered to the book’s timeline.

Mabel at age five. Mabel Dodge Luhan Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

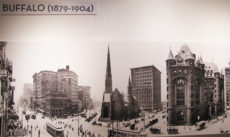

Downtown Buffalo, early 1900s. Exhibition panel from Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company. Courtesy Harwood Museum of Art

Born to wealth on February 26, 1879, Mabel Ganson grew up in Buffalo, New York at the height of the Gilded Age. Then the eighth largest US city, Buffalo was an industrial and economic powerhouse. Its location at the eastern end of Lake Erie and the terminus of the Erie Canal made it a major transportation center. Combined with a network of railroads, this infrastructure spurred tremendous growth in industry and manufacturing. Steel and lumber mills, sugar and oil refineries, breweries, tanneries and numerous other enterprises flourished.

Banking and business had established the Ganson-Cook family’s social and economic prominence. Mabel’s parents Charles and Sara Cook Ganson inherited the family fortune. In the 1880s and 1890s Buffalo boasted sixty millionaires (billionaires in today’s economy). The majority lived in grand mansions on Delaware Avenue, the city’s most prestigious address. Residents included lumber and railroad founder Frank H. Goodyear and leather-trade magnate Bronson Rumsey, whose children would become Mabel’s childhood friends.

We all needed to love each other and to express it, but we did not know how.

Ganson family home, 675 Delaware Avenue, Buffalo, NY. Collection of The Buffalo History Museum, used by permission

The Gansons lived at 675 Delaware Avenue. Mabel called it “a home destined for sorrow.” A particular example showed the state of her parents’ marriage. When her mother returned from a trip, her father lowered the flag to half mast. Product of a loveless marriage, Mabel couldn’t recall her mother ever kissing her or showing affection. Her father only gave her “dark looks and angry sound.” In Victorian times the wealthy elite typically left childrearing to governesses and nursemaids. Mabel’s domain was the third floor. She was the only family occupant. Lacking parental interest, she took comfort in touching mother goose figures that papered the walls of her nursery.

Books sent my clamorous spirit into another world. They have been accumulating and passing through my hands ever since.

Mabel found refuge in books. They piled up as soon as the grown-ups around her discovered that her passion for reading kept her occupied. She pored over “The Arabian Nights and all the fairy tales Hans Anderson and Grimm’s.” She repeatedly savored Alice in Wonderland, a book that provided “a departure from reality.” Books featuring the famous illustrator Howard Pyle not only added to her reading pleasure, they fostered her appreciation for fine art illustration and book design. Pyle’s colorful renditions in Robin Hood may have also awakened Mabel’s adventurous spirit.

Even with all its melancholy, my childhood had a wild, sweet, enthralling zestfulness.

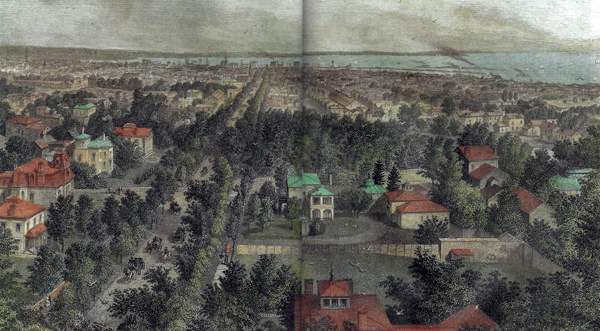

The City of Buffalo, 1873. Ganson Home with red mansard roof – 2nd from left – was across from Rumsey estate (front center). Courtesy Western New York Heritage Press, WNY Heritage Collection

One of Mabel’s earliest playmates was Nina Wilcox. She liked playing with Nina because she “could make Nina do just as I liked.” Mabel’s mischievous schemes often included Nina and other children. While her exhibitions of “power, prowess, and courage” impressed them, they often dismayed the adults. One instance involved prying house numbers off neighborhood homes. For weeks local newspapers carried the story of mysterious vandals making off with the numbers. When Frank “Grouch” Goodyear delivered a “box of candy” to Mabel late one night, her father discovered two of the “vandals.” He ushered Frank and Mabel to the police station the next day.

Statue of Seneca Chief Red Jacket (Otetiani, c.1758–1870), 1884, Forest Lawn Cemetery, Buffalo, NY. Wikimedia Commons

Mabel roamed the Delaware Avenue area with neighborhood children. They frequented the nearby Rumsey garden park, and ice skated on the pond. When her Cook grandfather gave her a pony and a tiny two-wheeled cart, she took Nina Wilcox and other girls around with her. Galloping as fast as Cupid could run, they drove out to the Forest Lawn Cemetery. Renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead designed the park. Mabel and her friends played there. There Mabel encountered her first Indian: the 12-foot-tall statue of the famous Seneca Chief, Red Jacket.

In the 1890s two individuals offered Mabel new possibilities. Buffalo painter Rose Clark taught art classes at St. Margaret’s Episcopal Girls’ School. Mabel took drawing lessons from her. Fascinated by someone so different, Mabel visited Clark in her studio on Saturdays. She viewed some of the artist’s paintings of children. Later Clark achieved some notoriety for her work. Alfred Stieglitz ranked her among ten foremost pictorial photographers in his 1902 Century Magazine article. Mabel also credited her. “I learned how to see with Rose Clark … without knowing it or meaning it, [she] taught me also her way of life.”

Untitled II , circa 1903. Platinum print by Rose Clark (1852-1942), probably with Elizabeth Flint Wade (1849-1915). Burchfield Penney Art Center, Buffalo, NY, Gift of Miss Frances Hamill, 1981

Nothing had ever deepened me or opened such wide gates as Violet and what she gave me. A whole new world of personalities and experiences in the books and music in her little salon.

Violet Shillito. Mabel Dodge Luhan Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

At age sixteen, Mabel met the second of her early mentors. In June 1896, she visited Violet Shillito, the sister of a school friend, in Paris. Violet, “a precocious embodiment of Pre-Raphaelite looks and sensibility, was learned in Latin, Greek, French and Italian.” Bookshelves set into the salon’s paneled walls held green and red leather-covered volumes. These ranged from Greek classics to contemporary works by George Sand and Gustave Flaubert. Mabel devoured these. She and Violet read Balzac together. In the small salon, with its brocade-covered chairs and Louis XV tables, Violet played Beethoven for Mabel on the grand piano. Sometimes after dinner, she played Chopin by candlelight. The music of Richard Wagner heightened Mabel’s musical experience that summer. She and the Shillitos traveled to Bayreuth to hear the Ring Cycle. The Opera House resounded with “herculean sounds falling all about us in cascades.”

Pierrefonds Chateau, ca. 1874-90

Mid-summer Mabel joined the Shillitos at the Chateau de Pierrefonds outside of Paris. There she and Violet vowed their mutual love. By moonlight in a “natural harmony emanating in rapid singing waves,” they shared “an overflow of increased life.” Mabel had never known anyone with such wisdom and love as she found in Violet. “I would love her best of all the world.”

Tragically, Violet died of diphtheria at age twenty-four. She had cultivated la grande vie interiéure (an inner life of spiritual beauty) and the pursuit of art “for life’s sake.” Her life teachings lived on in Mabel.

Mabel in “coming out” dress, 1898. Mabel Dodge Luhan Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Sensibilities garnered from these female exemplars led to Mabel’s first artistic achievement. Her debut into society would be different. Rose Clark helped Mabel transform the Twentieth Century Club’s characterless ballroom into a Baronial Hall. Banners and coats of arms hung next to great family portraits in the style of Rembrandt and Velásquez. Huge seats and tables, stained black, provided seating.

Mabel wore the latest French chic, a white satin dress with billowing folds of white net. After she and her mother received the thousand guests at ten o’clock, the ball got under way. “Fin de siècle clothes of the nineteenth century blended, with the help of punch and champagne (that flowed like water, my dear!), into the background of the Middle Ages. Mabel refused to dance. She either sat or strolled around the room. She smiled until her face stiffened. Finally, at 5 a.m. her father abruptly halted the festivities. The Gansons returned home.

“Well, that’s over with,” sighed my mother as she sailed into her room and left me to mount up one more flight. I was “out.”

* * * * *

Next in this series: Mabel in Florence, 1904-1912

SOURCE NOTES: With the exception of the quote from Lois Rudnick about Violet’s Pre-Raphaelite looks (in the book Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company), all quotes are in Mabel’s words from Background.

New York: Harcourt Brace & World, first edition 1933. Volume one of four of Mabel’s autobiography.

With a nod to Buffalo, New York, and its cultural institutions. Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company: American Moderns and the West exhibition will be on view in Mabel’s home town at the Burchfield Penney Arts Center March 10 to May 28, 2017.